As a 17-year-old in the year 1922, Anita Brenner enrolled in the University of Texas. Her experience of Austin had quite an impact on her and motivated her to return to Mexico, the country of her birth. There, with renewed confidence and the mentorship of J. Frank Dobie, she immediately embarked on a broad range of activities that would quickly gain her international acclaim and influence. Austin’s Dr. Alberto Garcia’s role in this has been briefly alluded to in my book The Life and Times of Dr. Alberto G. Garcia: physician, Mexican Revolutionary, Texas Journalist, Yogi. Here I provide a fuller account of how Austin’s occultists, including perhaps Dr. Garcia, changed Ms. Brenner’s life.

Childhood witness to the Mexican Revolution in Aguascalientes

As a child living in her birthplace of Aguascalientes, Mexico, Anita’s nanny, Nana Serapia, opened her eyes to the world of spirits and ghosts. When Anita was five years old, the Mexican Revolution broke out following the celestial displays of Halley’s Comet and the Centennial Comet. Anita remembers Nana telling her that these comets heralded terrible things to come. Under the leadership of the Spiritist and yogi Francisco Madero, however, the victory of the Mexican Revolution over the dictator Porfirio Diaz was swift. The year after Halley’s Comet, when revolutionary leader Francisco Madero set foot in Mexico City as the newly-elected president, an earthquake shook the ground and put cracks in the National Palace which had been the headquarters of the tyrant Diaz. Nana told Anita that this earthquake meant that a wicked era was over. Madero participated in séances and engaged in a type of automatic writing; through these activities, spirits had predicted his unlikely ascendency to the presidency and also predicted his later downfall.

President Madero was assassinated less than two years after assuming office, by generals in league with the United States Ambassador. The Mexican Revolution started back up again to oust a new dictatorship. Anita’s childhood eyewitness accounts of the revolution as seen from her parents’ home in Aguascalientes were quite vivid. Her father was a Jewish immigrant from Latvia and had been successful enough to own and operate a ranch. Anita became an admirer of Pancho Villa after his army, the Division of the North, arrived in Aguascalientes. She was ten years old.

They came confident still, singing ballads of their triumphs….. The Division of the North traveled in the manner classic to Mexican revolutionaries. Troop trains scrambled and trudged in ceaselessly, bristling with soldiers, gorged to the windows with women and spoils that spilled out on the roof and the ground….

They camped in front of our house, a soldier to a tree. His woman unrolled the blankets and spread a petate on the roots, drove nails into the trunk for hats and dug out a niche for an image. If you adventurously walked the avenue you had to be careful or you’d step on somebody’s baby and dive into somebody’s stew. Sometimes when the women quarreled … they rolled over and over in the dust, their hands buried in each other’s hair, biting scratching, dirty skirts flying and beads scattering, till the men, tired of this amusement (which didn’t end, like a cock-fight) roughly pushed them apart.

There was always the sound of bugles and the shuffled march of sandaled feet; always the smell of scorching frijoles and prickling chile, always the rattle of gossip, always the patter of women’s hands making tortillas and never a moment there was not the wail of a new child and the haunt of an old song……

A great tourist hotel across a field from our garden was turned into a hospital. One day we had the medical staff and some officers to lunch. The doctors, odorous of their make-shift calling ate hardboiled eggs out of the shells with their knives, and told tales…tales of limbs gangrened and hacked off in the quick, without anesthetics (there were none) with a flip of a machete ……

This last paragraph gives a flavor of what the practice of medicine was like for Dr. Alberto Garcia during the Revolution. He worked in field hospitals serving Venustiano Carranza’s army two years earlier, in 1913, at a time when Pancho Villa was aligned with him.

Anita Brenner attends the University of Texas in Austin

The Mexican Revolution continued without resolution, and Anita Brenner’s family fled to San Antonio, Texas. This was a year after Dr. Alberto G. Garcia and his family had fled to Austin from Mexico on a horse-drawn wagon. Starting from scratch, Anita’s father sold plants and sundries, slowly building a large nursery and the San Antonio’s first major discount store. He became the owner of the Continental Hotel.

When Anita was 17, she enrolled in the University of Texas in Austin, starting the fall semester of 1922. She was very unhappy there. Austin’s government was in the process of being taken over by the Ku Klux Klan, with its hatred of Mexican immigrants and Jews. Landlords operating rooming houses, refused to rent to Jewish UT students. She was a social outcast, later writing: “I was a lonely, absurd awkward person. I felt ugly and stupid. I was ignored. I resented and hated everything. A bewildered, unhappy nobody.”

There were bright spots that highlighted Anita’s intellect and presaged her future careers. Anita took an English writing class from folklorist J. Frank Dobie and he became her lifelong friend. She also joined the staff of the UT student newspaper, the Texan.

Four years earlier, Dr. Alberto Garcia also had taken journalism classes at UT and had also written for the Texan. He then created La Vanguardia, a weekly that was the first Spanish-language newspaper in Austin. La Vanguardia ceased publication a year before Anita Brenner arrived in Austin. Anita certainly would have known about La Vanguardia. And Dr. Garcia was well known for his fearlessness in resisting the Ku Klux Klan, for his supportive coverage of the Magonistas, Zapatistas, and other Mexican Revolutionaries, and for his denunciations of United States imperialism. Like Anita, Dr. Garcia had experienced the Mexican Revolution first-hand. It is hard to imagine that Anita Brenner and Alberto Garcia would not have met each other.

The homesick Anita Brenner would have found solace at Dr. Garcia’s large two-story 19th-Century home on Newning Avenue in South Austin at the literary and social events hosted by him and his wife Eva for Mexican students at UT and St. Edwards College. Dr. Garcia provided coverage of one of his parties the year before in his own newspaper: “the informal social gathering of young Mexicans from the university and young ladies from the Mexican neighborhood of Austin at the home of Dr. Alberto G. Garcia” was initiated by the singing of the Mexican National Anthem. “Other Mexican songs were sung by some of the young people in attendance. Tamales, atole, and capirotada bread pudding were served.” Dr. Garcia may have provided Anita Brenner with her first introduction to vegetarianism. Dr. Garcia had been raised in the home of America’s most influential vegetarian, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, and received his initial medical degree from Dr. Kellogg’s medical school. Later in life, Anita too would become a vegetarian.

Voice of a Prophetic Spirit

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

After the end of her second semester at UT, Anita Brenner attended a séance at a home she later vaguely described as being at the edge of town. Dr. Garcia’s home was on the other side of the River from UT and most of the rest of the town, surrounded by empty wooded lots and a mere nine blocks from the southern city limits. Some of the neighborhood public school students arrived barefoot from shacks along the creeks and hills outside the City limits; they were children of the clannish cedar choppers who spoke an Elizabethan English dialect. Dr. Garcia indeed lived at the edge of town.

Dr. Garcia probably was one of Anita’s few trustworthy social contacts. It is possible that the séance took place in the Garcia home, and if so, it would have been appropriately discreet for Anita not to identify the eminent Garcia’s as the hosts. Dr. Garcia had long been an astrologer and now was initiating a serious but secret life-long interest in such things as yoga and magic rituals evoking spirits and gods.

Anita arrived at the séance after it had begun. A voice called out to her:

You do not believe, and your pain is greater because you have no faith. Your heart is rebellious, and you set your own spirit as the only reality.

Today life is terrible for you, you are a rebel in futility. But you shall go to a strange land, and there many men will want you, and you shall see many things that only lofty spirits know. You will reach truth if you have faith…. Through your hand you will tell to the world many radiant things, for you have the gift and need only your faith. Peace be with you.

When the séance was over, Anita went home and immediately made arrangements to leave Austin. She returned to her family in San Antonio, and after her 18th birthday moved to Mexico City.

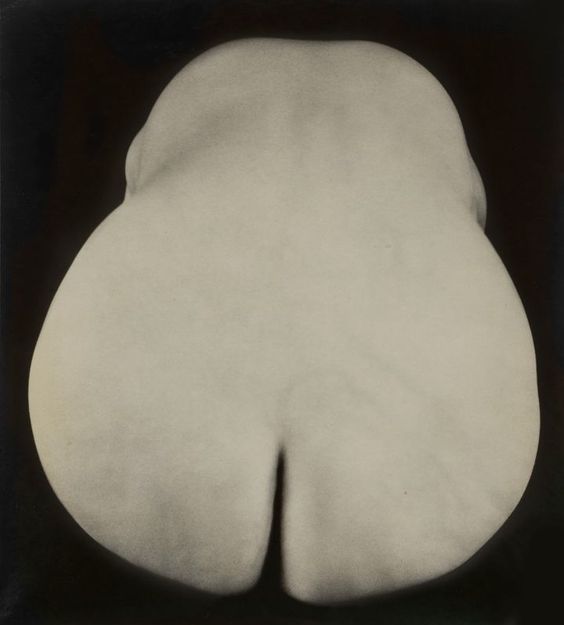

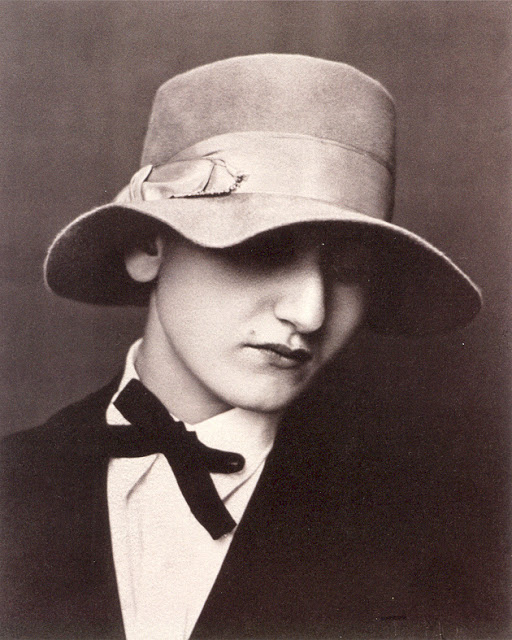

Within weeks of arriving in Mexico City, Anita wrote to Austin friend Geraldine Aron about her new community of artists, “sculptors, writers, socialists, musicians, poets …. No snobbishness, prejudice, of any sort—racial, monetary, apparent.” Among her many Mexico City friends and acquaintances were the painter Jose Clemente Orozco, Mexican Feminist Party founder Elena Torres, balladeer Concha Michel, and Maria Sandoval de Zarco, the only practicing female lawyer in Mexico. Friends Edward Weston and Tina Modotti used her as a model in some of their iconic photos. She developed a close and long-standing friendship with Diego Rivera, and later became friends with Frida Kahlo.

Rivera had deep connections to the spirit world. Present at his birth was his mother’s uncle, a Spiritist. In the 1920s, Rivera was a member of the Mexico City Rosicrucian lodge, and as Anita Brenner noted, Rivera’s “sister is a clairvoyant and he believes in apparitions and ghosts.” The sister was a folk healer and performed limpia ceremonies on Anita to remove evil spirits.

Whereas in Austin, Anita had been a wallflower, many men in Mexico did want her professionally and personally, as predicted by the Austin spirit prophet. “That love is free is a matter so accepted that no one ever thinks to bother to state so,” she wrote. The prominent artist Jean Charlot pursued Anita and she enjoyed flirtations and seductions with boyfriends. Not that she was the most attractive or alluring woman in Mexico City. In a diary entry she expressed envy of Tina Modotti and the diffuse joy Tina received from her “numerous cohabitations.”

After a lunch with her friend Concha Michel, Anita wrote the following:

We have the same philosophy, which recognizes sex as the key to things, and the plane upon which woman’s position is placed—and should be. Since it is creative energy, it is for her to direct it. To be able to do so, she herself must be physically pure. Therefore vegetarianism.

Like Concha, Diego Rivera, Edward Weston, Mexican Communist Party head Rafael Carrillo, US Communist exiles Bert and Ella Wolfe and others (including Dr. Alberto Garcia) with whom she broke bread, Anita became a vegetarian

In Mexico City, Anita Brenner became a prolific journalist, an art critic, and an assistant to Manuel Gamio, who was the top anthropologist in Mexico and a Rosicrucian. At the age of 21, three years after leaving Austin, Anita Brenner began researching and writing a pathbreaking book that when published three years later would become both influential and acclaimed. Idols Behind Altars celebrated and explained to the world Mexican art and its underlying indigenous spirituality. One of the Mexican artists Anita wrote about was Fermin Revueltas, who had attended St. Edwards College in Austin for one semester in 1917. Another book followed—a history of the Mexican Revolution called The Wind That Swept Mexico.

Anita went to Columbia University in New York in 1927 where she became friends with fellow student Margaret Mead. Anita earned a Ph.D. in anthropology under Franz Boas (the leading anthropologist of the era) – all without first ever having received a college undergraduate or master’s degree.

In 1929, while a New York student, she picked up a Bible to see what it might have to say about the ancient history of Chaldea and Babylonia. Spontaneously, out of nowhere, Anita was seized by a profound transcendent experience.

I had the queerest of sensations, which mentally were translated into question and answer, much as this: Question: But what exactly must I do with my abilities…. Answer: Pick up the thread of uncompromising spiritual and ethical thought, which means fight against almost everything in modern thought around you … which also means keep yourself as pure and lofty of mind as you can. [The experience] grew and grew and I had feelings of faintness and a tremendous sensation of being out of the world…. If I had seen anything “supernatural” I would not have been in the least surprised. That was my mood…. And then I got a sensation of reluctance, because I realized the full implications of what the proposal was … and I nearly said aloud, “No, no, I am just an ordinary normal craftsman,” and I got burning sensations in my mouth … and not until I “submitted” did it stop; after which I was thoroughly exhausted.

Anita continued spiritual pursuits. After her friend and former Pancho Villa lieutenant Manuel Hernandez Galvan was murdered, she contacted him and carried out a conversation with him through a Spiritist automatic writing technique.

In June of 1926, Diego Rivera had come over to her Mexico City apartment and the two had a long talk. She wrote, “At midnight I was exalted and converted.” She had become a revolutionary. In 1932, Anita read the Bolshevik Leon Trotsky’s autobiography: “What a book and what a man. Inevitably getting more and more interested in things Marxian.” The next year Anita interviewed Trotsky in Paris where he had gone to avoid Stalin’s assassins. Trotsky predicted “a great war (I do not speak of a small preventative war)” initiated by a rearmed Germany. And the transition from capitalism to socialism, prophesied Trotsky, would be measured in generations, not years.

From New York Anita Brenner devoted herself to international efforts to get a fair trial for nine African American boys convicted by an all-male and all-white jury in Alabama of raping a white woman. In reversing the convictions, the U.S. Supreme Court established new precedent in recognizing both the constitutional right to counsel and the unconstitutionality of the exclusion of African Americans from juries.

In 1933, Anita was interviewed by a female journalist who wrote that the petite, “vivacious, dark-haired Anita Brenner looks more like a college girl than a full-fledged author, registered anthropologist with a Ph.D from Columbia. She greets her guests in green lounging pajamas, topped with a brightly flowered coat. She bubbles with girlish enthusiasm, talking eagerly and shaking her short curls.” That same year, Anita Brenner went to Spain as a war correspondent for The Nation and the New York Times Magazine. The newly-established democratic government of Spain was threatened by fascist and other right-wing forces. She found in Spain a country similar to Mexico, but in a continuing state of revolutionary transformation. The Leftist government was supported and armed by the government of Mexico. She wrote:

The most thrilling thing in Spain are the workers. Revolution and all that really means something here. Makes all our [United States] intellectuals’ committees and the ILD look awfully silly, because from this perspective it is plain that we were doing everything in a vacuum, and all the people who were doing it were miles away from being workers.

The genocide perpetrated by General Franco’s fascist forces (and fueled by Texaco oil and equipped by Adolph Hitler’s Germany) took a horrific toll on the Spanish democratic forces. If this were not enough, Anita Brenner (now pregnant in 1936) took note that Joseph Stalin’s Communist newspaper Pravda had announced from Moscow: “As for Catalonia, the purging of Trotskyites and the Anarcho-Syndicalists has begun; it will be conducted with the same energy it was conducted in the U.S.S.R.” Anita publicized the clandestine prisons and the assassinations managed in Spain by Stalinist operatives like Tina Modotti’s lover Vittorio Vidali. Anita exposed some of the activities of her former friend Tina Modotti as a Stalinist agent.

Returning to New York City in 1938, Anita and her husband threw a famous Day of the Dead Halloween Party attended by Frida Kahlo, philosopher-educator John Dewey, artist and designer Isamu Noguchi, and the ghostly Whittaker Chambers who had just left the Communist Party and was hiding out, fearing assassination. During this time, Anita was also writing a column for Mademoiselle magazine.

Anita Brenner defended and sought refuge for many socialists targeted by Stalin and Hitler. She played a critical role in helping protect Stalin’s greatest opponent, Leon Trotsky. When she learned that Trotsky’s latest country of asylum had a new government with a Nazi SS Minister of Justice, she contacted Diego Rivera and convinced him to petition the President of Mexico to grant Trotsky asylum. Asylum was granted and Trotsky moved into Diego Rivera’s and Frida Kahlo’s home in Mexico City. Following an affair with Frida Kahlo, Trotsky moved into his own compound, where one of Stalin’s agents finally breached his security and killed him with a pickaxe as he worked at his desk.

Anita Brenner never forgot Austin. The Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas holds a first edition copy of Anita Brenner’s 1943 book The Wind That Swept Mexico: The History of the Mexican Revolution. The book is autographed by her and inscribed to J. Frank Dobie.

The racism, anti-Semitism, and parochialism of Austin during the years 1922 and 1923 had made Anita miserable. Yet an Austin séance she attended showed her a way out, filled her with confidence, and instantaneously propelled her into a future unforeseeable to anyone outside of the spirit world. At the séance, a spirit’s voice acknowledged her deep alienation in Austin and called her to greatness in another land where “many men will want you, and you shall see many things that only lofty spirits know” and “tell to the world many radiant things.” Whether she heard this voice in Dr. Alberto Garcia’s home or heard it in the home of one of the Spiritualists, Theosophists, Rosicrucians, Hermeticists or Oddfellows inhabiting Austin during those years, the prophecy turned out to be both accurate and transformative for Anita Brenner.

In the last years of her life, Anita returned to her family farm in Aguascalientes and revived it. After her death, Anita was not forgotten in Aguascalientes. Some years after her passing, an apparition said to be her was reportedly observed, according to her daughter, “about three feet off the ground…playing with children at the low-income housing project built on the farm’s orchards. [S]he instructed the children to plant trees, to love and respect the earth.”

Sources

Brad Rockwell, The Life and Times of Alberto G. Garcia (2020). Susannah Joel Glusker, Anita Brenner: A Mind of Her Own (1998); Margaret Hooks, Tina Modotti (1993); Mexico Modern (Albrecht & Mellins, eds., 2017); Austin City Directory (1922).

#AnitaBrenner #AustinTexas #JFrankDobie #MexicanRevolution #DrAlbertoGGarcia #TinaModotti #Edward Weston #Frida Kahlo #DailyTexan #LeonTrotsky #Spirits #seances